Clarence Thomas and John Roberts Are at a Fork in the Road

Two years ago, when the Supreme Court decided New York State Rifle and Pistol Association, Inc. v. Bruen, it created a jurisprudential mess that scrambled American gun laws. On Friday, not only did the cleanup begin, but the Supreme Court cleared the way for one of the most promising legal innovations for preventing gun violence: red flag laws.

The Bruen ruling did two things. First, it rendered a sensible and, in my view, correct decision that the “right of the people to keep and bear arms” as articulated in the Second Amendment includes a right to bear arms outside the home for self-defense. But the right isn’t unlimited. As Justice Brett Kavanaugh wrote in his concurrence in Bruen, the court did not “prohibit States from imposing licensing requirements for carrying a handgun for self-defense” and that “properly interpreted, the Second Amendment allows a ‘variety’ of gun regulations.”

At the same time, the court articulated a “text, history and tradition” test for evaluating gun restrictions in future federal cases. Under this test, gun control measures were constitutional only if the government could demonstrate those restrictions were “consistent with the Nation’s historical tradition of firearm regulation.” That was the most significant element of the Bruen case. Before Bruen, lower courts had struggled to establish a uniform legal test for evaluating gun restrictions, and the Supreme Court hadn’t provided any clarity.

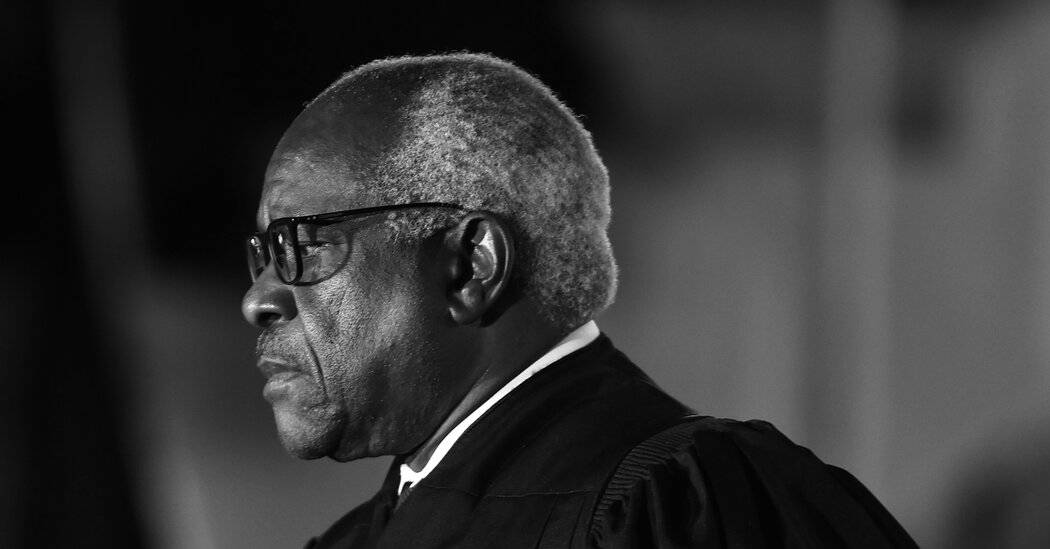

Justice Clarence Thomas wrote the majority opinion in a 6-to-3 decision split along ideological lines. He applied the text, history and tradition test by walking through the very complex, often contradictory, history of American gun laws to determine whether New York’s restrictions had analogies with either the colonial period or in the periods following ratification of the Second Amendment and the Fourteenth Amendment, which applied the Second Amendment to the states. Under a fair reading of Thomas’s opinion, lower courts would be hard pressed to uphold any gun restriction unless you could point to an obvious historical match.

Not only was the history messy, but judicial reliance on founding-era legislation suffers from an additional conceptual flaw: State legislatures are hardly stuffed with constitutional scholars. Then and now, our state legislatures are prone to enact wildly unconstitutional legislation.

Our courts exist in part to check legislatures when they go astray. They do not rely on legislatures to establish constitutional doctrine. In our divided system of government, legislators are not tasked with interpreting constitutional law. Yes, they should take the Constitution into account when they draft laws, but the laws they draft aren’t precedent. They do not and should not bind the courts.